Dr. William E.

Thomas

De Mortuis Nil Nisi Bene?

On Alleged Karl May’s Mental Illness

Many comments have been made on the creativity of persons with

exceptional ability and of highly original kind. It is not possible to

conclude that exceptional literary, musical or scientific work is the

result of mental disorder. There are however some important or famous

personalities about whom it is known or is presumed that they suffered

with full or mild form of bipolar disorder. In such cases there are of

course during the severe disturbances intermissions in their creative

activities. Milder depression and hypomania usually do resemble in their

literary or other work. In some writers, poets and dramatists,

depression is thought to be the source of tragic or sad themes.

Hypomanias on the other hand the inspiration for comedies and joyful

plays.

Any judgment in this field is to be made

with extreme caution, in particular if sufficient knowledge of

circumstances is not known. Such informations are very scarce especially

with historical personalities. Great care is required because it is a

subject that for the general public carries a taste of sensationalism.

Many people do not look for the explanation of influences that contribute

to outstanding creative work. They are misusing such studies looking with

selfsatisfying smirk for anything to denigrate the life and work of an

outstanding personality. In this way they often bring injury to the living

and damage to the memory of the deceased.

There has been a suggestion put

forward[1] that Karl May might have suffered from

manic-depressive illness known today under the name of bipolar disorder.

It is difficult to see how anyone who had read and studied the books and

life of Karl May would be able to agree with this thought.

(1) Bipolar disorder – cause, general course and

common treatment.

Bipolar disorder (manic-depressive

illness) is a chronic disease that persists throughout one’s life. It is

a mental illness involving episodes of serious mania and depression.

Bipolar disorder is extremely distressing and disruptive not only for

the patient, but also to people around him or her. It cannot be cured

but can be well controlled nowadays through the use of psychotherapy and

medication such as Lithium. Without treatment the symptoms will persist

and worsen, and ultimately hospitalization may be required. If untreated

bipolar affective disorder is associated with high suicide rate[2]. Eighty percent of patients with bipolar disorder

presented with major depression and only developed a manic episode

during their second or third episode of illness.[3]

The diagnostic features of bipolar mood

disorder are outlined in ›The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorder‹, Fourth Edition (Washington DC, 1994), known as DSM-IV.

In order to make a diagnosis of

bipolar mood disorder the symptoms must »cause clinically

significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other

important areas of functioning«[4]. The

symptoms must not be »due to the physiological effects of drug abuse, a

medication, other treatment for depression, or toxin exposure. The

episode must not be due to the direct physiological effects of a general

medical condition.«[5]

Bipolar mood disorder is usually

classified into subgroups: Bipolar I., Bipolar II. Cyclothymic Disorder,

Hypomanic Episode, Manic Episode, Mixed Episode, and Major Depressive

Episode.

Bipolar

I. is characterized as the occurrence of one or more manic

episodes or mixed episodes with duration of at least one week. Many

such patients also experience at least one major depressive episode.

Ten to 15% of bipolar affected people commit suicide or become violent

during severe manic episodes. Job failure, divorce, substance

(alcohol) abuse and antisocial behaviour are common. The most

susceptible to this disorder are the first-degree biological relatives

of bipolar I affected people.

Bipolar

II. »The essential feature of bipolar II disorder is a

clinical course that is characterized by the occurrence of one or more

major depressive episodes accompanied by at least one hypomanic

episode«[6]. The presence of manic or mixed episodes would

nullify the diagnosis of bipolar II. Those with a first degree

biological relative that is affected by bipolar II are at heightened

risk for developing bipolar I, bipolar II, and for experiencing major

depressive episode than the general population.

Cyclothymic

disorder – »The essential feature of Cyclothymic disorder

is a chronic, fluctuating mood disturbance involving numerous periods

of hypomanic episodes and numerous periods of depressive symptoms«[7]. First degree biological relatives of those

affected by cyclothymic disorder are at increased risk of being

affected than the general population.

Manic

episodes are characterized by »a distinct period of

abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive or irritable mood«[8].

Hypomanic

episode is characterized by a distinct period of

»abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood

that lasts at least four days«[9]. The criteria are

essentially the same as that for a manic episode except that delusions

and hallucinations cannot occur. In addition, the person’s mood must be

markedly different than their usual, nondepressed mood, and there must

be an uncharacteristic change in their level of functioning.

Mixed

episodes – people experiencing mixed episodes appear to

meet the »criteria for a manic and for a major depressive episode

nearly every day«[10].

Major

depressive episode is defined as a »depressed mood or loss

of interest in nearly all activities«[11].

Duration must be at least two weeks. Symptoms are inability to

concentrate, difficulty in thinking and making decisions, decreased

energy, and recurrent thoughts of death, suicide ideation, plans, or

attempts.

What

causes bipolar disorder? Not much is known about the causes

of this disorder. A chemical imbalance (low or high level of specific

neurotransmitters such as serotonin, norepinephrine or dopamine) in

the brain (a link exists between neurotransmitters and mood disorder)

is found in bipolar affected people. It is known that first-degree

biological relatives of affected individuals are at heightened risk

for bipolar disorder. However not everyone with a predisposition to

bipolar is affected. A severe life stressor is needed to activate the

disorder, such as physical, mental, environmental or emotional causes.

Considering the biological

explanation, inheritability is to be addressed. This question has been

researched via multiple family, adoption and twin studies. In families

of persons with bipolar disorder, first-degree relatives, i.e. parents,

children, siblings, are more likely to have bipolar disorder[12][13][14].

Medication in Bipolar Disorder.

The Australian psychiatrist John

Cade discovered the therapeutic effects of Lithium carbonate against

mania in 1949. In the early 1960’ period anti-depressant drugs were

becoming available for general psychiatric use[15].

One important factor has to be

kept in mind. During the time of Karl May’s life there was no effective

treatment available for bipolar disorder. Even today the psychosocial

outcomes are poor in many patients with bipolar disorder[16].

Latest findings challenged the view that bipolar disorder occurred in

distinct episodes with little residual deficit once patient recovered.

It appears that 30 – 60% of individuals with this disorder failed to

regain full functioning in occupational and social domains. There was a

significant level of unemployment, poor social contact and impaired

social adjustment between episodes of acute illness. This would have

been even more pronounced in Karl May’s lifetime when there was no

efficient medication available.

(2) Examples of people suffering from bipolar

disorder.

Charles

Burgess Fry, the remarkable sportsman, was born in 1872,

captained the English cricket team, played soccer and rugby for

England, broke world long jump record which he held for 21 years and

was a deputy delegate at the League of Nations Assembly in 1919.

CB Fry won the Greek prize as an

undergraduate at Oxford, where he topped the list of first class honours

in classics. In 1919 he was offered the crown of Albania, but because

there was no salary, he declined. To do all this must have taken not just

talent, but a quite unusual hyperactivity.

The first odd thing to surface was in

1895, the year after all his university triumphs. Fry could only manage a

fourth class in Literae Humaniores and played cricket very poorly. It was

said he was depressed due to his mother’s illness, but Fry was withdrawn

and depressed for five years! He bounced back in 1901 to score centuries

in six consecutive cricket innings, a record never surpassed, but equaled

38 years later.

Fry was a great talker and bon vivant.

He spoke with machine gun rapidity and dominated any conversation. Fry was

at ease discussing anything from iambic pentameters to the niceties of

long past cricket games. Then in 1929, aged 57, came the crash. On a visit

to India Fry became paranoid, believing the locals were out to steal his

possession. When brought home Fry was secretive, withdrawn and would not

let his belongings out of sight – apart from one occasion when he was

caught running naked down the beach. A full-time nurse was employed and

for about three years Fry neither met people, offered opinions or

discussed his feelings.

In 1933 he emerged and once more became

the witty raconteur and racy commentator of old. He resumed his job of

running the merchant naval training ship Mercury. The ship’s discipline

attracted the attention of the emerging Adolf Hitler, and Fry was invited

to advise on the organization of Germany’s youth. Little came out of it.

During World War II Fry was appearing on

BBC radio’s discussion group The Brain Trust. The chairperson had

difficulty shutting him up. At age 70 Fry stated he wanted to go in for

horse racing and was asked: »What as – trainer, jockey or horse?«

Fry is regarded by many as the greatest

sportsman England has produced. He showed all the stigmata of a quite

severe bipolar affective disorder.

Manic Music Composers.

Handel

was notorious for his major moodswings, and is known to have written

his gigantic oratorio, ›The Messiah‹, in six weeks. Another composer,

Rossini, spun out ›The Barber of Seville‹, one of the

major operas of the nineteenth century, in thirteen days. Critics have

computed it would be hardly enough simply to copy the opus in that

time span. Rossini’s musical career peaked with ›The Barber of

Seville‹ and he then went on to a dry spell that lasted some fourteen

years. During this time he produced nothing. When he began to compose

once again, the work was of inferior quality. The composer Robert

Schumann was manic-depressive, and his cycles of creativity

are documented. He was elated during the whole of 1840 and 1849 and

these were the peak years of his musical output. When Schumann was in

deep depression, he stopped composing altogether. In 1854, after his

major creative phase, he tried to drown himself in the Rhine, but was

rescued, only to spend his remaining two years of life in hospital.

(3) Chart of Life – Literary Output and Events in

Karl May’s Life.[17]

The life and work of Karl May have been

documented elsewhere. Only events that might have influenced May’s mental

state are noticed here. The record of May’s literary output year by year

shows there was no period of deep pathological depression in which he

would not have been able to concentrate on writing.

1874:

Die Rose von Ernstthal

1875:

Wanda

Das Buch der Liebe

Der Gitano

In-nu-who

Ein Stuecklein vom

Alten Dessauer

Die Fastnachsnarren

Schaetze und

Schaetzgraeber

Old Firehand

Geographische

Predigten

May lived with his parents in Ernstthal.

He accepted the position of an editor in Dresden.

1876:

Auf den

Nussbaeumen

Leilet (Die Rose

von Kahira)

Im Wollteufel

Der beiden

Quitzows letzte Fahrten

Ausgeraeuchert

Unter den Werbern

Im Wasserstaender

May leaves editor’s job with

Muenchmeyer’s publishing company and became acquainted with his future

wife Emma Lina Pollmer. He commuted between Dresden and Hohenstein.

1877:

Der Samiel

Der Kaiserbauer

Die verhaengnißvolle

Neujahrsnacht

Die Gum

Der Oelprinz

Ein Abenteuer auf

Ceylon

Die Kriegskasse

Aqua benedetta

Auf der See gefangen

Ein Selfman

Emma Pollmer moves to Dresden. Their

financial situation was poor and May has to borrow money. In Juni May

finds another job as an editor.

1878:

Der Ducatennest

Der Afrikaander

Husarenstreiche,

Schwank

Der Kaiserbauer

Der Teufelsbauer

Die drei Feldmarschalls

Vom Tode erstanden

Die Rache des Ehri

Die verwuenschte Ziege

Nach Sibirien

Der Herrgottsengel

Die Laubtaler

Die Rose von Sokna

Fuerst und Reitknecht

Die falschen

Exzellenzen

Rather impressive literary output.

May lives in Dresden with Emma Pollmer. He finds time to make enquires

into the death of Emma’s uncle (›Stollberg’s affair‹). The whole

official protocol that includes May’s statements to the judge has been

preserved and published[18]. May travels on business in Germany. In July May

quits the editorial post and moves back to Hohenstein.

1879:

Die Universalerben

Des Kindes Ruf

Der Waldkoenig

Die beiden

Nachtwaechter

Der Gichtmueller

Der Giftheiner

Unter Wuergern

Der Ehri

Three carde monte

Der Boer van her Roer

Der Pflaumendieb

Ziege oder Bock

Scepter und Hammer

Der Girl-Robber

Fuerst und Leiermann

Im fernen Westen

Der Waldlaeufer (Free

translation of the novel by Gabriel Ferry)

A quarrel with Emma Pollmer. Three weeks

detention in Ernstthal (1–22 September) as the result of ›Stollberg’s

Affair‹.

1880:

Im Sonnenthau

Deadly Dust

Ein Fuerst des

Schwindels

Die Juweleninsel

Tui Fanua

Der Scherenschleifer

Der Kiang-lu

Der Brodnik

Emma Pollmer’s grandfather dies in May.

In August Karl May and Emma Pollmer marry, church wedding follows in

September. The couple moves into a house in Hohenstein.

1881:

Ein Wuestenraub

Die Both Shatters

Giolgeda Padishanun:

Abu el Nassr

Die Tschikarma

Abu Seif

Eine Wuestenschlacht

Der Merd-es-Scheitan

Der Ruh’i Kulyan

Reiseabenteuer in

Kurdistan (2 End)

Ein Fuerstmarschall als

Baecker

The ›Deutscher Hausschatz‹ starts the

›Karl May legend‹. May is still a private person.

1882:

Ein wohlgemeintes

Wort

Robert

Surcouf

Christi Blut und

Gerechtigkeit

Saiwa tjalem

Der Krumir

Die Todeskarawane

In Damaskus und Baalbek

Das Waldroeschen (1882–1884)

In summer Emma and Karl May meet H.G.

Muenchmeyer. May agrees to write for his publishing firm, partly because

of his wife’s insistence but also because of their poor financial

situation.

1883:

Die Liebe des Ulanen

(1883–1885)

Im »Wilden Westen«

Nordamerika’s

Stambul

Ein Oelbrand

Pandur und

Grenadier

The May’s move from Hohenstein to

Dresden.

1884:

Der verlorne Sohn (1884–1886)

Der letzte Ritt (1884

u. 1885)

Karl May is fully occupied writing

novels for Münchmeyer’s publishing firm.

1885:

Deutsche Herzen,

deutsche Helden (1885–1888)

May’s mother died on the 15 April.

In May his father suffered a stroke. Karl May went through a period of

bereavement. He was able to continue writing by May. A major depression

cannot be substantiated[19].

1886:

Delila(h) (Fragment)

Der Weg zum Glueck (1886–1888)

Unter der Windhose

Still fully occupied writing novels for

Muenchmeyer’s publishing house.

1887:

Durch das Land der

Skipetaren

Der Sohn des

Baerenjaegers

Ein Phi-Phob

Das Hamail

Ibn el ’amm

1888:

Maghreb-el-aksa

Der Geist der Llano

estakata

Der Scout

Kong-Kheou

May terminated his writing for

Muenchmeyer. May’s father died in September. Emma and Karl May move

several times to different addresses.

1889:

El Sendador I: Lopez

Jordan

Die Sklavenkarawane

Sklavenrache

May lives and writes in private. Other

stories are being published in journals only. Emma and Karl May get to

know Klara and Richard Ploehn.

1890:

El Sendador II: Der

Schatz der Inkas

Der Schatz im Silbersee

May is unable to pay the rent »even if

he hardly leaves the writing desk.«

1891:

Der Mahdi

Das Vermaechtnis des

Inka

Christus oder Muhammed

Die beiden Kulledschi

The publisher Ernst Fehsenfeld visits

May with the suggestion to bring on the market his stories in book’s

editions. Agreement concluded in November. The money advance by Fehsenfeld

enables May to pay outstanding debts. Because May was a chain smoker he

suffered from frequent upper respiratory tract infection, influenza or

exacerbation of bronchitis.

1892:

Mater dolorosa

Im Sudan

Durch die Wueste

Durchs wilde Kurdistan

Von Bagdad nach Stambul

In den Schluchten des

Balkan

Durch das Land der

Skipetaren

Der Schut (with a new chapter on Rih’s death)

May’s financial situation has improved

through cooperation with Fehsenfeld. May feels more secure and wrote in a

letter to a reader in December as part of public relation exercise: »I am

telling what really happened, and the people I am talking about really did

exist or are still alive today. F.e. I myself am Old Shatterhand.«

1893:

Die Felsenburg

Der Oelprinz

Eine Ghasuah

Nur es Sema –

Himmelslicht

Der Verfluchte

Winnetou I.

Winnetou II.

Winnetou III.

Das Testament des Apachen

Der Pedlar

Orangen und Datteln

Am Stillen Ozean

An der Tigerbruecke

Karl May became extremely popular with

the book edition of ›Winnetou‹. During a visit to Fehsenfeld in June the

marital friction between Emma and Karl May came to fore in public.

1894:

Krueger Bei

Am Rio de la Plata

In den Kordilleren

Old Surehand I.

Maria oder Fatima

Christ ist erstanden!

May suffers from repeated bounds

of bronchitis complicated with chest infection. Perhaps to avoid the

tense situation with Emma at home the pair travels in Germany. In

November May wrote to Carl Jung that he speaks 25 languages with some

additional dialects. May later (1904) elaborated on what he meant[20].

May was in touch with his readers through letters mostly. His private

life he kept to himself.

1895:

Die Jagd auf den

Millionendieb

Old Surehand II.

Im Lande des Mahdi I.

Blutrache

Der Kutb

Visit by Ferdinand Pfefferkorn from the

US who introduced them to spiritism, then in vogue in America. The

popularity of his books helped May financially. He bought in November a

house in Radebeul, which he named »Villa Shatterhand.«

1896:

Der schwarze Mustang

Freuden und Leiden

eines Vielgelesenen

Im Lande des Mahdi II.

Im Lande des Mahdi III.

Tut wohl denen die euch

hassen!

Die letzte Sklavenjagd

Old Surehand III.

Satan und Ischariot I –

III

Er Raml el Helahk

Der Kys-Kaptschiji

With the permanent address of »Villa

Shatterhand Radebeul« Karl May became a public figure and could not any

longer keep in touch with his readers by letters only. To keep in line

with the image he created, and to cater for the curious and inquisitive

public, Karl May bought the Silver gun and the Bear Killer gun from a

Dresden gunsmith. He kept them on display in his Villa for the visitors to

see. May also had 101 photos taken of himself in the costumes of Old

Shatterhand and Kara ben Nemsi. The photos were on sale to his readers.

However when on holidays in

August-September in Lorch am Rhein, staying with the family of wine

merchant Jung, Karl May never talked about his books. When asked

directly May – as Carl Jung junior reported later[21] –

»…questions on details about his travel experiences he as a rule

sidestepped with a short dismissive answer, so that I shortly found out

that he did not wish to be very communicative in such matters.«

In this year Karl May also wrote

›The Joy and Suffering of a Popular Writer‹. This excellent

self-description enables a unique view into Karl May’s mind[22].

1897:

To-kei-chun

Old Cursing-dry

Im Reiche des Silbernen

Loewen

Auf fremden Pfaden

Ein Blizzard

Weihnacht!

Life became hectic for Emma and Karl

May. The popularity of his books reached a cult status. The public at

large identified Old Shatterhand with Karl May. More and more readers

wished to see Old Shatterhand in his Villa, just as nowadays admirers of

Elvis Presley flock to Graceland.

»Large crowds of visitors« wrote Emma May in a letter

from 16. October, »the bell rings every three minutes, a servant girl has

to stand at the gate all the time.« And later »We had again two American

ladies visiting us; since we came home, we had so far no peace.« And again

»Countess Jankovics for a couple of days, then a visit from Berlin,

Hamburg, Warsaw … There were f.e. so many strange people here that in the

evening we had, counting the local acquaintances, 26 people at the table.«

»On the three X-mass days we had altogether 43 people at the table.«

May was his own public relations and

business manager. What he used to write in letters to his readers May now

was telling to his visitors. Dr. Fr. Amroth who visited May in January

mentioned how the discussion touched mainly what was in the books and what

the public wanted to hear from the author himself. The only way how to

escape the visitors was to go travelling. This however showed to be no

solution: »The word Karl May is here spread through the neighbourhood like

a lightning…« (6 June at Koenigswinter). Karl May was aware of his role

and of business obligations, when he did not want to be photographed at

Komotau (13 July), claiming that the publisher of his books has the

exclusive rights to his photos.

After return to Radebeul in August

Emma May wrote in a letter: »… for as long as we are home, we had no

peace.« Karl May became »The darling of his readers«[23].

The pair May escaped to Birnai in Bohemia (26.10-17.11), where May

finished writing the »Weinacht« undisturbed.

1898:

Scheba et Thar

Im Reiche des silbernen

Loewen

Ein Raetsel

Indianische Mutterliebe

The ›Prager Tagblatt‹ reports in

February when Karl May visits on business the publisher Vilimek in Prague:

»Dr.Carl May, the known globe trotter and writer, known to readers under

the names Old Shatterhand and Kara ben Nemsi…« Certainly a good

advertisement for May’s books. Karl May was in good control of himself

when he declined the offer to try the famous organ at Emausy cloister in

Prague! [May also declined to meet with a visiting group of Arabs.] Later

that month May participated at a carnival in Vienna’s casino in a

discussion with baron Vittinghoff-Schell, had a lecture on Winnetou,

talked with the members of the Austrian imperial family, some of whom were

avid readers of his books, met with members of his fan clubs.

1899:

Am Jenseits

Die »Um ed Dschamahl«

In March Karl May departed

Radebeul for his Orient trip. The often-quoted »psychotic states« during

his trip (in Padang and Istanbul) cannot be substantiated[24].

1900:

In July May returned to Radebeul.

1901:

Et in terra pax

Der Zauberteppich

Himmelsgedanken

On 14 February Richard Plohn died.

1902:

Am Tode

Im Reiche des silbernen

Loewen III.

Scheitans-Weib-Wueste

In March tense domestic situation, May

stays overnight in a hotel. Klara Plohn becomes May’s secretary in April.

In August Emma agrees to a divorce.

1903:

Im Reiche des

silbernen Loewen IV.

Sonnenscheinchen

Das Geldmaennle

In January divorce legally confirmed. In

February Klara Plohn and Karl May marry. In March follows church wedding

at Radebeul. In November May’s prison record released by court causing a

severe stress reaction to him.

1904:

Und Friede auf Erden

Weltall – Menschheit –

Krieg

»The lively, good natured stories of the

famous, much appraised and maligned man and his spirited, faithful lady

companion in life, captivated listeners in high degree« reported

›Donauwoerter Anzeigenblatt‹ on 27 October on a lecture May held at the

local school.

1905:

Ein Schundverlag

An article ›The King of Swindlers‹

appears in June in a Dresden newspaper.

1906:

Babel und Bibel

Kyros

Briefe ueber Kunst

1907:

Schamah

Der Mir von Dschinnistan

Bei den Aussaetzigen

Frau Pollmer, eine

psychologische Studie

May’s health deteriorates; stay at Bad

Salzbrunn in May-June. In November house search by authorities in

connection with court proceedings. In November the psychiatrist Dr. Paul

Nacke pays a visit to May in Radebeul.

1908:

Meine

Beichte

Abdahn Effendi

Klara and Karl May visit Prague; Berlin

in June. In September travel to America, where May delivers a lecture in

Lawrence on 18 October.

1909:

Winnetou IV

Ardistan und

Dschinistan I/II

Ein Schundverlag und

seine Helfershelfer

In December delivers a lecture at an

educational institute for English ladies.

1910:

Mermameh

Mein Leben und Streben

An die 4. Strafkammer

des Koenigl. Landgerichtes III in Berlin

Egon Erwin Kisch visits May in

Radebeul[25].

1911:

Stay at Joachimsthal.

1912:

On 22nd March lecture in Vienna. Karl May dies at Radebeul on 30th

March.

(4) Could pathological

depression or mania be documented in Karl May’s life?

Most people with bipolar disorder

do have periods of depression at some time of their lives. There

is no evidence Karl May had suffered from Major Depressive Episode

that would be acceptable as a psychiatric diagnosis as outlined in

DSM-IV.

Looking at the literary output

year by year by Karl May there was one period in 1885 when he was not

able to concentrate on writing. On 15 April 1885 May’s mother died. May

was not able to deliver to the publisher the weekly contribution of

articles until the middle of June. He was going through the stage of

bereavement, a grief reaction[26].

The paper (1) quotes as a proof of

May’s major depression a letter written by May to Fehsenfeld in 1893:

»my nervousness … because of domestic discord … that I often look above

my writing desk where a loaded revolver hangs«. However the year 1893

was a very successful year for Karl May. He was becoming very popular

because of the book edition of ›Winnetou‹. The public was conditioned to

match Old Shatterhand with Karl May in the tradition started by the

›Deutscher Hausschatz‹ publicity buildup. This was a year of May’s

achievement and greatly improved financial situation when he had no

reason to become depressed. But the relation between Emma and Karl was

quickly deteriorating[27]. It was a time of marital clashes with his wife

Emma, which were becoming more public. May also mentioned a revolver

in a letter to Professor Dr.Paul Schuman in 1904[28].

May used this as a figure of speech, an act of dramatization, not as an

expression of suicidal intention.

May’s clear description of his

bodily pain in 1910[29] is interpreted in paper (1) as part of his life

lasting cycles of depression. In fact the pain was of organic origin[30].

The statement from (1): »Sleep disturbances, which May in his old age

interpreted as a symptom of his depressive ill-feeling, were permanently

present in his creative and also hypomanic phases …«[31]

incorrectly assumes mental illness. It was bodily pain that made May

feel miserable in his last years. Many people study, concentrate and

write better at night. This is simply a working habit and not a mental

disease. Connecting old age and depression as part of May’s long

lasting bipolar disorder is incorrect. The author of (1) did not take

into consideration organic causes for depression including for example

dementia, Huntington’s chorea, temporal lobe epilepsy and Parkinson’s

disease. An organic cause should in particular be considered when the

mood disorder is presenting in an elderly person[32].

In such way the author of (1) missed the cause of the chronic pain May

suffered from.

The unsubstantiated psychotic

condition Karl May was supposedly having during his Orient journey in

Padang and Constantinopol, is presented in (1) as evidence of May’s

bipolar disorder. Firstly the concept of ›psychosis‹ in itself is not

diagnostic. Secondly the story of May’s psychotic breakdown has not been

confirmed[33]. Another statement from (1) that May »was searching

for an explanation of his cyclic mood swings that he did not understand«[34] is wrong. Clear description of manic-depressive

states was part of all psychiatric textbooks during May’s lifetime.

In ›Meine Beichte‹ May wrote he

suffered from ›Depression‹ during his ordeal in 1860s. The traumatic

amnesia and hallucinations May described as experiencing himself at that

time however speak against major depressive state. Other typical

symptoms of major depression as ›changes in appetite and weight‹

described by May during his Orient voyage were in connection with his

dysentery. ›Changes in sleep and psychomotor activity‹ – the sleep

pattern of working during the night and sleeping longer into the day was

May’s long life working habit. There was no prolonged period of

›decreased energy or inactivity‹ if we inspect the list of May’s yearly

literary output. Nothing corresponds with the pattern of people with

bipolar disorder who become incapacitated sometimes for years. This

applies also to ›difficulty in thinking, concentrating or making

decisions‹, and also for pathological ›feelings of worthlessness or

guilt‹. The quoted poem in (1) by Karl May »I am so tired …« written

during the Orient voyage was just that, an expression of loneliness, sad

mood, and not a sign of deep incapacitating depressive state.

It seems that the main argument in

(1) for Karl May’s bipolar disorder is May appearing in public in the

years 1893-1900 and after. This is classified as ›hypomanic-manic

episodes‹[35]. From the description given May supposedly suffered

for whole of his life from ›long-lasting hypomania‹[36],

even well into his old age[37]. That condition, it is claimed in (1), was faintly

but distinctly overlaid with episodes of depression[38].

Such version given in (1) of Karl

May’s mental state would be more accurately described by a psychiatrist

as Cyclothymic Disorder: »The essential feature of Cyclothymic Disorder

is a chronic, fluctuating mood disturbance involving numerous periods of

Hypomanic Episodes and numerous periods of depressive symptoms«[39].

However the diagnosis offered in (1) is Hypomanic and Manic Episodes,

characterized by a distinct periods of abnormally and persistently

elevated, expansive, or irritable mood that lasts at least four days[40][41],

and are interfering with daily life.

There are certain observations of Karl

May’s conduct which speak against the classic symptoms of untreated mania:

-

There are no reports of manic

behaviour as known from descriptions of untreated patients, when they

become violent even suicidal and have to be restrained or

hospitalized. The often quoted ›psychosis‹ during Karl May’s Oriental

journey showed to be unsubstantiated. There are no documented periods

of time during which Karl May would not have been able to work or

function in the society because of severe depression, hypomanic or

manic states.

-

No verbal garbage was ever

recorded as it happens in acute mania, where there is a typical

flight of ideas in which connection between one idea and the next is

based on chance association including similar sounds (the clang

association)[42]. In all preserved reports of Karl May’s public

appearances his speech was coherent, even if multiloquacious.

-

It was the ›Deutscher

Hausschatz‹ which started the build-up of Karl May’s public image,

the ›Karl May legend‹, when the editor published the following: »The

author of the adventure travel stories visited himself all the

countries which are the scenes of his stories. He returned recently

from a journey to Russia, Bulgaria, Constaninopel, etc., and even

suffered a knife wound as a souvenir. He however does not enjoy to

travel with the red Baedecker [travel guidebook] in hand and via

railway compartment, but he seeks the less known routes«[43].

May continued later on in this

tradition. Claus Roxin in his study ›Dr.Karl May called Old Shatterhand‹[44]

put forward four possible reasons for May’s behaviour after 1890: (a)

May played the role of Old Shatterhand to conceal his past. (b) May was

more or less forced into the role of Old Shatterhand by his readers. (c)

It was on the part of Karl May a business self-promotion. (d) May’s

conduct was an expression of narcissistic neurosis. Lately (1) put

forward a thesis of bipolar disorder as the cause of May’s performance.

The (b) and (c) reasons seem to explain

Karl May’s conduct, as the diagnosis of hypomanic or manic psychiatric

disturbance is not tenable.

The question of hereditary trait in Karl

May’s ancestors.

The (1) mentions also the

possibility of family history as a contributing factor to May’s bipolar

disorder. May’s grandfather on mother’s side, one Christian Friedrich

Weise, was found hanged in 1832. The cause of his death according to the

official entry into records was »drunkenness and despair«.[45]

In the absence of sufficient information about Ch.F.Weiss and the

circumstances of his death, it is hardly justified to connect him with a

psychiatric diagnosis.[46]

It is known that the first-degree

relatives are more likely to have a genetic predisposition to bipolar

disorder. Even if May’s father was known for his bad temper, he was not

manic-depressive, never had been hospitalized or under psychiatric care.

In order to prove that genetic

factors play a part it must be shown that near relatives of the mentally

ill are more often also mentally ill than are the members of the general

population, and that this cannot be explained by common environment.

Both twin studies and the family studies, however, indicate that there

really is often a genetic predisposition and that on the whole this

predisposition is specific. One type of mental illness only tends to

occur within one particular family[47].

In family studies it was found that the proportion of first degree

relatives of manic-depressive patients who are also affected with

manic-depressive insanity is of much the same order, though a little

less than the proportion of like-sex fraternal twins. Stenstedt

carried out one of the best studies[48] in

Sweden. He took as his starting point all instances of

manic-depressive psychosis from two areas of Sweden from 1919 to 1948.

Stenstedt found that of the brothers and sisters 7 per cent were

certainly affected and another 7 per cent possibly affected. For

parents the proportions were 5 per cent and 7.5 per cent, for children

11 per cent and 17 per cent. The actual manifestation of the illness

varied in different members of the same family. The family study

suggested that patients with many attacks and patients with few

attacks, patients with mainly manic symptoms and patients with mainly

depressive symptoms, patients with an early onset and those with a

late onset of the illness, all had varieties of essentially the same

disorder, since all these varieties might occur within a single

family.

To confirm the alleged

manic-depressive illness in Karl May more studies of his family members

would have to be done. If one examines the incidence of manic-depressive

illness in the relatives, it is higher than in the general population.

The incidence falls away dramatically as the degree of relationship, and

the genetic resemblance, becomes more remote[49].

The first generation of offspring’s is at risk; the second generation

carries less ›dominant‹ traits[50].

These facts have been recognized today and are included into the

DSM-IV, where the first-degree biological relatives are named as being

at heightened risk for developing Bipolar I, Bipolar II, and for

experiencing Major Depressive Episode more than the general

population. Studies on close relations, identical twins and adopted

children whose natural parents have bipolar disorder strongly suggest

that the illness is genetically transmitted, and that children of

parents with bipolar mood disorder have a greater risk of developing

the disorder.

What the paper (1) puts forward as

support for May’s bipolar disorder[51] is

insufficient to support the thesis. It certainly does not confirm the

first-degree biological relatives known facts. More research into May’s

family tree with particular attention to the incidents of mental

abnormalities would be required before the expressed view in (1) could

get any credit at all.

The author of (1) named his essay

›Author in Fabula – Karl Mays Psychopathologie …‹. Why the presumption

of mental abnormality? Is it because it simply follows in the German

tradition of maligning one of their most successful and popular writers?

The blindness of May as a child is declared an »ophthalmologic

impossibility«[52], even if this is not correct and cannot be

substantiated. From such a false premise the author concurs with the

view that Karl May was a psychopath, a pathological liar[53].

On the basis of May’s critics he is described as having a »bizarre

personality structure«[54]. Again the negative damaging assessment of Karl

May, based on what his critics and enemies said one hundred years ago.

Karl May himself answered his critics[55]

but his words are not mentioned in the essay.

Karl May correctly assessed his reaction

to the trauma he suffered in his early manhood, as requiring medical

attention and not prisons terms. This has been overlooked again. Almost

all authors – including the (1) – did not pay attention to what May said

himself, believing he was a liar, but tried to present May as a neurotic,

narcissistic personality, psycho-neurotic, and finally even mentally

imbalanced manic-depressive. Always the negative about Karl May, all the

time an insistence that May was abnormal in some way.

The author of (1) does not see the

period 1862–1874 in May’s life as the time of stress and May’s reaction

to it. He calls it a period of »criminality and hoboeism of May as an

expression of personality disorder«[56].

He considers it not to represent a reaction to

life events, but to be an expression of May’s deviation of normal

cognition[57], turning Karl May into a morally insane

personality. The author of (1) also claims May was »lying as a rule in

all the time new varieties«[58]. This should have been happening from May’s youth

to his old age. To demonstrate May’s bad character the author of (1)

creates a non-existent love affair with a married woman[59]

to stress the moral insanity of a nineteen years old May.

Marital conflicts are the most

difficult situations to deal with. What is not mentioned in (1) in

connection with May’s ›Frau Pollmer, eine psychologische Studie …‹ is

the fact that Emma Pollmer suffered from mental illness[60]

and had to be hospitalized because of it later in life. Klara May’s

diary describes Emma’s behaviour in some detail which is quite

informative.

Episodes from the life of Karl May

are presented in (1) as psychiatric symptoms, f.e. discussions with the

readers of his books which were distorted and incorrectly reported, as

May points out in his letter to a newspaper in Dresden[61].

Giving tips to waiters and domestics is presented as sign of

megalomania – when charity by Karl May is not mentioned at all[62].

Sending postcards from May’s Oriental journey is classified in (1) as

manic behaviour, when in fact it was a sound promotional public relation

exercise.

In such way a psychiatric

diagnosis was artificially created. There were no major incapacitating

depressive episodes or significant hypomanic or manic impairments in

important areas of functioning documented in Karl May’s life. A

diagnosis of bipolar disorder as outlined in DSM-IV cannot be sustained.

Karl May was a successful creative writer and his own business and

public relations manager. He was an artist, not a certifiable mental

case.

|

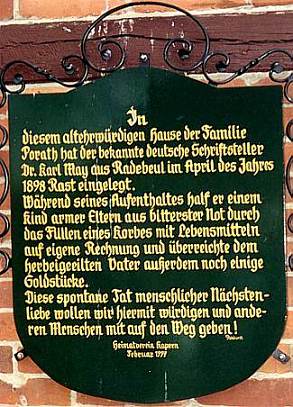

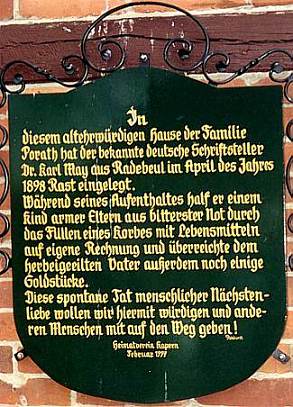

In this dignified old

house of Porath family took rest in April 1898 the famous

German writer Dr.Karl May from Radebeul. During his stay he

helped a child of poor parents in their bitter need by filling

up a basket with food at his own expense, and also gave the

father of the child, who rushed in, some gold coins. We wish

to honour herewith this spontaneous deed of human charity, as

an example to others.

The Shire of Kapern,

February 1997

|

|

Photo:

Hartmut Kühne |

References

Please click on the hyperlinked reference numbers to return to your

place in the text.

[1]

Johannes Zeilinger: ›Autor in Fabula‹,

Dissertation University Leipzig, 1999.

[2]

Untreated, manic-depressive illness is

associated with a suicide rate of approximately 20%. In: OMIN

(Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man) John Hopkins University –

Major Affective Disorder: Manic-depressive Psychosis. Gene map locus

2001.

[3]

Prof. Gordon Johnson -Department of

Psychiatry at the University of Sydney – in: Australian Doctor 28

July 2000.

[4]

DSM-IV, p.336.

[5]

DSM-IV, p.336.

[6]

DSM-IV, p.359.

[7] DSM-IV,

p.363.

[8]

DSM-IC, p.328.

[9]

DSM-IV, p.335.

[10] DSM-IV,

p.333.

[11] DSM-IV,

p.320.

[12] Davis,

S.F.& Palladino, J.J.: ›Psychology‹ (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle

River, NJ; Prentice Hall Inc. 2000.

[13] The

Old Order Amish of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, US, has been used

to study a form of manic-depressive disorder and linkage related to

genes: Egeland, J.A. et alii: ›Bipolar affective disorder linked to

DNA markers on chromosome 11‹. Nature 325: 783-787, 1987. Also:

Gelemter, J.: ›Genetics of bipolar affective disorder – time for

another reinvention?‹ (Editorial) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 56: 1262-1266,

1995.

[14] Using

positron emission tomographic (PET) images of cerebral blood flow

and rate of glucose metabolism to measure brain activity an area of

decreased activity has been localized: Drevets, W.C. at alii:

›Subgenual prefrontal cortex abnormalities in mood disorders‹.

Nature 386:824-827,1997.

[15] Fieve,

R.: ›Moodswing – The Third Revolution in Psychiatry‹, William Morrow

& Co. USA 1975.

[16] Acta

Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2001; 103:163-70.

[17] The

time line of Karl May’s writings has been taken from: »Ich«,

Karl-May-Verlag, Bamberg 1992; Ralf Harder: Karl

May und seine Muenchmeyer-Romane, Ubstadt 1996; Siegfried

Augustin: Vorwort zum KMG-Reprint ›Frohe Stunden‹, Hamburg 2000.

[18] Maschke,

F.: ›Karl May und Emma Pollmer‹, Karl-May-Verlag Bamberg 1973.

[19] Thomas,

WE: Karl May’s Bereavement.

[20] Karl

May: ›An den Dresdner Anzeiger‹, JbKMG 1972, p.139.

[21] Volker

Griese: ›Karl May Stationes eines Lebens‹, Sonderheft der KMG

Nr.104/1995, under August 1896.

[22] Wilhelm

Brauneder: ›May ueber May: Ein »Vielgelesener« – kein

»Vielgereister«!‹

[23] »Der

Liebling der Leserwelt« – in: (21) under September 1897 – quoted

from ›Deutscher Hausschatz‹ Nr.49.

[24]

Thomas, W.

E.: Karl May in the German Tradition.

[25] Kisch,

E. E.: ›Hetzjagd durch die Zeit‹, Aufbau Taschenbuch Verlag GmbH,

Berlin 1994; pp.71-97 – »In Wigwam Old Shatterhands«.

[26] See

under (19).

[27] Maschke,

F.: ›Karl May und Emma Pollmer‹, Karl-May-Verlag Bamberg 1972,

pp.55-56.

[28] Karl

May: ›An den Dresdner Anzeiger‹, JbKMG 1972, p.14.

[29] Karl

May: LuS 299-300.

[30]

Thomas, W. E.: Karl

May’s Last illness and Cause of Death.

[31]

»Schlafstoerungen, die May im Alter als Symptom seiner depressiven

Verstimmung deutete, waren in seinen kreativen und auch

hypomanischen Phasen permanent praesent, …« In (1).

[32]

Gerard, A; Johnson, G; Storey,C: ›Bipolar Disorder – could it be

organic?‹ Current Therapeutics, Vol.41, No.4 (April 2000), pp.79-81.

[33]

Thomas, W. E.: Karl

May in the German Tradition.

[34] »May

suchte hier offensichlich nach einer Erklaerung fuer die ihm

unverstaendliche zyklische Schwankung seines Gemutszustandes« in (1)

2.6.4.

[35]

»Hypomanich-manische Episoden« – (1) 2.6.3.

[36]

»langdauernden

Hypomanie« – in (35).

[37]

»blieben diese

hypomanische Zuege bis ins Alter erhalten«.

[38] »matter

und deutlich ueberlagert von depressiven Episoden.«

[39]

DSM-IV, p.363.

[40] DSM-IV,

p.335.

[41] DSM-IV,

p.328.

[42]

If for example a patient from Kingstown

is asked »Where do you live?« the answer comes as: »King, King

staying, see the King he’s standing, king, king, sing, sing, bird on

the wing, wing on the bird, bird, bird, not heard, turd …« etc.

[43] ›Deutscher

Hausschatz‹ No.9.

[44] Jb-KMG

1974.

[45]

»Trunkenheit u. Verzweiflung«

[46] It

is almost impossible to state a diagnosis in similar cases: Clothes

and rag dealer Dorothy Handland was »in a fit of befuddled despair«

when, at the age of 84, she hanged herself from a eucalyptus tree in

Sydney Cove (Australia) in 1789. Two years earlier she had left

England on the First Fleet after being sentenced to seven years’

transportation for perjury. Dorothy not only earned a dubious honour

in Australian history by being the oldest female convict on the

First Fleet, but also by being the first person to commit suicide in

the new colony of New South Wales. Although no medical records are

available, modern commentators have speculated that she may have

been depressed and possibly had dementia. Perhaps she had a serious

physical illness that could not be adequately treated, and

consequently made life unbearable in the rough and poorly resourced

new settlement. (Hughes, R.: ›The Fatal Shore‹, Pan Books 1988,

p.73.)

[47] Carter,

CO: ›Human Heredity‹, Penguin Books Ltd, London 1967, p.224.

[48] In

(47), p.226.

[49] Withers,

R.: ›Heredity‹, Hamlyn London 1972, p.134.

[50] Beadle,

G&M: ›The Language of Life‹, Anchor Books New York 1967, pp.

62-63.

[51]

»Familienanamnestische Aspekte der affektiven Stoerung« – (1) 2.6.5.

[52] »eine

ophthalmologische Unmoeglichkeit« – 2.1.3.

[53] »

diese Psychopathie … pathologicher Luegner …« – 2.1.4.

[54] »eine

bizarre Persoenlichkeitsstruktur« 2.2.

[55] In

(20).

[56]

»Kriminalitaets- und Vagantenphase Mays als Ausdruck der

Persoenlichkeitsstoerung« – 2.5.2.

[57] »

seine Abweichung von der normalen Kognition sich wie ein roter Faden

durchs Leben zog, stabil bis ins Alter blieb … nicht nur in der

Jugendzeit, auch im Alter hatte diese Stoerung …« – 2.5.2.

[58] »er

leugnete regelmaessig in immer neuen Varianten« – 2.5.2.

[59] »eine

Liebesaffaere mit der Ehefrau…« – 2.5.2.

[60]

»Geisteskranke« – see: Maschke, F.: ›Karl May und Emma Pollmer‹,

Karl-May-Verlag Bamberg 1973, pp.122-123.

[61] In

(20)

[62] See

memorial plague by Heimatverein Kapern Februar 1997 on May’s present

in April 1898 to a child of poor parents of a food-basket and golden

coins.

Karl May aus medizinischer Sicht

Karl May –

Leben und Werk